In this episode of Cybersecurity (Marketing) Unplugged, Spafford also discusses:

- Who and what could be behind the pileup of attacks on security vendors;

- How our democracy and freedom of speech allow for exploitation by the adversary;

- Why our current solutions seem to create more problems than they solve;

- And the need for a bigger push to develop secure and resilient systems.

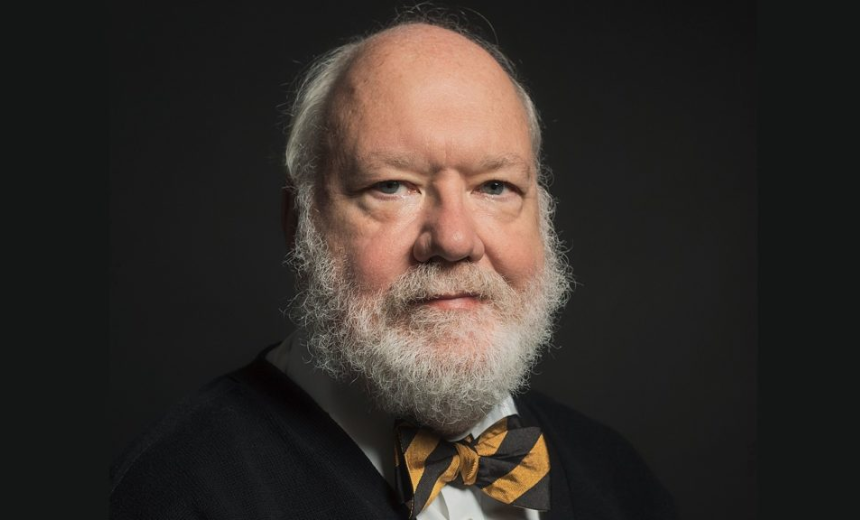

Eugene Spafford is a professor with an appointment in computer science at Purdue University, where he has served on the faculty since 1987. He is generally recognized as one of the senior leaders in the field of computing. In 2013, he was inducted into the National Cybersecurity Hall of Fame. He was recognized, in part, for his co-development of the first free intrusion detection system distributed on the internet and for originating the term “firewall.” Spafford is known for his writing, research and speaking on issues of security and ethics. He has brought that expertise to Washington, as a witness testifying before Congress and as a former member of the President’s Information Technology Advisory Committee. He also serves as executive director of Purdue’s Center for Education and Research in Information Assurance and Security.

To stitch existing security seams that are fraying at the edges, or to start over? That is the question. Eugene Spafford thinks there is a clear answer.

I got to wondering whether much has changed over the last year or so in the way we defend against cybersecurity attacks, so I did a quick revisit of our podcast with Eugene Spafford, whom some would argue is the Father of Cybersecurity.

When we talk about all the spending that’s been done on security, over the years, the vast majority of that has been patching and building new layers on top of broken artifacts. So fundamental problems continue to be present in the way we design and use those systems. And because there isn’t really a good set of metrics, and there aren’t sufficient disincentives organizations are unwilling to spend the money and the effort to build more resistance systems to replace the existing infrastructure with this huge sunk cost that’s out there. … So the way we’ve approached securing systems, has generally been wrong.

Full Transcript

This episode has been automatically transcribed by AI, please excuse any typos or grammatical errors.

Steve King 00:14

Good day everyone. I’m Steve King, the managing director here at CyberTheory, and today’s episode is going to explore the recent avalanche of cybersecurity breaches, and the ramifications and impacts going forward. Joining me is Jean Spafford, whom many, including me, considered the global preeminent expert in cybersecurity, and who After earning his master’s and doctorate in computer science from the Georgia Institute of Technology, went on to build Purdue University’s legendary cybersecurity program, where he remains today as a professor in computer science and also the Executive Director Emeritus at the Purdue University Center for Education and Research and Information Assurance and security. With a resume 40 studded with accomplishments for the time we have a lot in here, like his work that underlies a lot of cybersecurity mechanisms in use today, including firewalls, intrusion detection, vulnerability scanners, integrity, monitoring, forensics and security architectures. I think I’ll summarize by saying Spath, as he’s known is the only cybersecurity expert who’s both in the Hall of Fame served two US presidents, and delivered formal congressional testimony on cybersecurity nine times well, contributing to 10 Major amicus briefs before our US court system. To say the jean Spafford knows something about cybersecurity would likely be the understatement of the century. So welcome Spath. And thank you for joining me today.

Eugene Spafford 01:49

My pleasure.

Steve King 01:51

My first question would be What the heck is going on here? And we’ve just seen the six attack on leading cybersecurity vendors software in seven short weeks. How is this happening? And who is behind it?

Eugene Spafford 02:07

Well, those are two questions that have multi part answers. And let me just observe that what we’re seeing is reports of various kinds of attacks, and compromises. And that’s going on all the time. Sometimes it’s discovered, sometimes it’s not. The fact that we have a group of them all happening now isn’t quite so unusual. Sometimes when a high profile incident occurs. And people start probing their systems to see if they were affected, they find evidence of other compromises that it occurred are other vulnerabilities. So some of that may be behind what’s going on here. But the real issue here is, we have a lot of vulnerabilities. We have a lot of poor security. And it isn’t surprising that we continue to have a number of incidents. As to your question about who’s doing it? Well, lots of different groups, we have a lot of activity going on by criminals. We also have several nation states that are conducting espionage seeking advantage either for companies within their borders. So there’s a certain amount of espionage that is for national economic gain. And there’s also espionage going on for the sort of traditional political and military purposes. So number of actors, number of motives, all taking advantage of weaknesses in our overall infrastructure.

Steve King 03:41

Yeah, I’m sure that’s all true. I guess some folks like Richard Clarke would say that. This looks to him like Battlefield preparation. And we have various opinions all weighing in blaming the Russians. Is that a fair assessment in your mind? You know, the attribution issues are very difficult, of course, is there any indication given the pattern of these attacks that we could say anything for sure about the sources?

Eugene Spafford 04:10

Ah, the people who’ve analyzed some of these incidents have found what they believe to be very strong correlation with past behavior by some Russian groups that are connected with either the GRU or SVR in Russia, because of the nature of the flaws, and in some cases because of text found within some of the code. But attribution is difficult. So it’s not 100% certain, but at least the information that’s been made public seems to point in that direction. China also certainly conducts its share of intelligence gathering, although that’s seems mostly collecting information on Are people or economic data that they can use. So the targeting sometimes is a little different. The notion of preparation of the battlefield is also hard to gauge. The set of attacks that we’ve seen around the solar winds incident, for instance, were pretty targeted in terms of which sites, they actually probed. They use the distribution mechanism to gain a foothold on 10s of 1000s of systems and organizations, but only activated a smaller number of them, it appears to establish a longer term be shedding and do investigation. And we still aren’t quite sure what it was that they were after, at those sites. But it wasn’t a wide scale mapping kind of exercise from everything that I’ve seen.

Steve King 05:58

So what do you what do you expect thereafter, in this case, then,

Eugene Spafford 06:03

I think thereafter, strategic information. There are a number of reasons why traditional espionage is conducted. One is to discover, planning, strategic planning that affects not only the country conducting the espionage, but potentially their partners and targets. It is sometimes to establish whether or not their existing operations have been detected, and other venues. Sometimes it is simply to establish a long term presence, so that later if they need to collect that kind of information, they can go back and get it. Sometimes it’s to identify individuals or people where they can either exert leverage to conduct other kinds of espionage or potentially where they can. So disruption through Disinformation and Propaganda, which we have certainly seen a lot of in recent years. And there are other reasons, the actual motivations behind organizations can be quite extensive. And in part that’s understanding your opponent and, you know, maybe what their plans are. So in that case, for instance, the SVR is not the military intelligence agency, as much as the GRU is, and so they’re probably more interested in some of the political aspects and identifying those kinds of issues. But again, it requires deeper analysis and actually access to other intelligence that is likely classified, to be able to put together a better big picture.

Steve King 07:46

The disinformation misinformation, Mal information that you refer to has been sort of hit an all new high during the presidential election, you must have some insights about where that was coming from primarily. There was a lot of people, of course, blaming the Russians for all of that implement psyops. But I wonder how active the Chinese had been as well, because you know, if their objective if the objective of any of our adversaries is to divide this nation, that certainly worked out pretty well for them.

Eugene Spafford 08:16

Indeed, there is some evidence that there was some Chinese influence they have had and have interest in the trade embargoes that were carried out by the previous president. They’ve had concern about adverse publicity over the spread of the Coronavirus and great interest in what has been done with vaccines. So they certainly had at least a couple topics right off the top that were politically motivated that they’d be interested in. But there’s also evidence that other countries and parties were involved. So, for instance, there is evidence that Iran was also involved in helping to promote some divisive themes and social media. And, in general, this is the kind of interest of simply we’re getting an adversary getting information focused elsewhere. It may also be the case, for instance, that North Korea has been involved in disinformation for similar reasons.

Steve King 09:22

Well, I guess, folks like Keith Alexander would say that, as advanced and connected as we are also makes us maybe the most vulnerable targets, I suppose, on the planet. The question for a lot of people, though, you know, as we look at all of the spending that we do on cybersecurity, and the fact that the incidents continue to mount seems like the adversaries are getting better at their business and it appears as if we’re getting worse at our business. So what would you say has been missing in the way that we’ve been approaching cybersecurity defense?

Eugene Spafford 10:00

Well, I think there are two primary issues that sort of encourage this behavior. The first one is that we do have knowledge about how to build more resilient defenses. We do know how to build systems that are better protected. But it’s expensive to do that. And most of the existing deployed systems are based on mass market, lowest denominator, hardware and software. And so when we talk about all the spending that’s been done on security, over the years, the vast majority of that has been patching and building new layers on top of broken artifacts. So fundamental problems continue to be present in the way we design and use those systems. And because there isn’t really a good set of metrics, and there aren’t sufficient disincentives organizations are unwilling to spend the money and the effort to build more resistance systems to replace the existing infrastructure, we have this huge sunk cost that’s out there. And as a result, when problems occur, people rush around and oh, we need to have something to monitor that patch that fix that virtualize that. And we add yet another layer that itself has vulnerabilities. So the way we’ve approached securing systems, has generally been wrong. And there are economic reasons underlying that. When I’ve said this to some audiences, they go, Well, we can’t afford to replace everything. And the response is, well, we don’t have to replace everything. But we need to do a very careful assessment of what are the high value items. And those are the things that we should replace, rebuild, restructure to protect. So if we have a multinational corporation, it’s not necessarily the case that everything within that corporation needs to be replaced and fixed. But the really core important parts do. The second element is something that we haven’t really come completely to grips with. And I don’t know that we can easily. In the US, we have, for instance, great value on freedom of speech. Well, that’s used by opponents against us by planting and exacerbating fringe thought, conspiracy theory, hate speech. And we’re very vulnerable to that. They’re not so much because they censor what can be said, they clamp down on communications, that’s an issue. In our country, we have a separation between civilian and military, law enforcement. And some of our intelligence agencies or law enforcement agencies have restrictions on what they can observe and where their authority ends. That isn’t the case with a lot of our adversaries, they have these integrated attack and defense groups that can look inwards at their own citizens as well as outwards. So some of the things that we value in our society, provide seems where opponents can attack from a structural point of view. And I certainly don’t suggest that we change that. But we need to do a better job of understanding where those seams are and how to cover them in some way. We have authority split, FBI, NSA, DHS, state authorities, local authorities, and more. And it isn’t clear that they all work together. And there are some spots where nobody covers. So between those two, the economic issues, the technical issues, and simply the structural issues, we have a lot of weak spots.

Steve King 14:10

that paints a fairly bleak picture and you’re doing it diplomatically to so it’s even bleaker than one would take away based on what you just said. So from my view, what I heard you say was we’re unique Democrat Republic, our society is hinged to the tenets of our Constitution, which are completely the opposite of every one of our adversaries. And because of that, unless we change the constitution, and the principles upon which we’ve founded this country, we’re always going to be exposed and the fact that we have multiple agencies in the business of defending various different agendas, who do not work together, because you know, everything has been politicized these days. It doesn’t sound to me like there’s much Hope, regardless of what we do, from a technology point of view, much hope for changing the curve here.

Eugene Spafford 15:06

Well, writ large security as an unwinnable kind of pursuit, that we can’t ever be 100%, safe from all possible threats. That’s just a simple fact of the matter that we cannot spend enough, we cannot be alert enough, we do not have the resources to be able to prevent every kind of threat. What we need to do instead is to identify where the biggest risks are, and make sure that they are addressed in an appropriate manner. It is complicated by the fact we don’t fully understand the risks. The risks are created in part by private entities as well as public entities. So we have national security information, national infrastructure, that is run by private companies that are resistant to certain kinds of regulation and oversight. So that creates some issues, how do we address those, we haven’t done a good job of that. I have some hopes that the very talented cybersecurity team that has been recruited for the new administration can help make some progress on that we really haven’t done much over the last few years. As far as the technology goes, we really need to do a better job there as well. There are bright spots, there are places where we have employed good security, we know how to do it. But that knowledge and that willingness to spend for it has not been made as a case yet to some of the vulnerable places within our infrastructure where it shouldn’t be employed. So we have work to do, it’s not impossible. But it is going to require a willingness to change the way we do things, to get away from simply putting patches on things after the fact. And to start thinking proactively about how to protect ourselves.

Steve King 17:09

Yeah, I agree with your assessment of the new cybersecurity team that’s been assembled here under the Biden administration thus far. You know, I look back on the information from the 2005 era under George Bush, were, you know, I could have issued the same report today. So it’s 15 years later, we’ve had Obama we’ve had Trump and we’ve had 15 years worth of calendar to have adopted or to move in any kind of positive direction from National Cybersecurity point of view. And yet, we really haven’t, you know, and then, and then we turn around and fire Chris Krebs. You know, none of this makes a lot of sense in the way that the government has approached this. It can’t be a question of money, because, you know, we’ve spent frivolously all over the world here, so we’ve got plenty of money. I just, I’m not sure what the problem is. Do you have any insight today?

Eugene Spafford 18:04

Part of it is prioritization. Security is a difficult spend, in the sense that if I spend now on improving security, and then nothing happens, people question Why did we spend the money? The y2k situation is a great example. Yeah, it was a lot of concern, there was a lot of money and activity spent to make sure there would be no disaster. And when there was none, people afterwards, were going well, why were we so worried? Why do we spend so much you see this at some of the better performing organizations that don’t show up in reports of breaches and disasters? They spend on their security, and that’s the way they plan to do it. But there are people with those organizations as well. We’ve never been broken into why are we spending so much on security. Where we end up spending is after there’s been a crisis, after there’s been news of the big breach, or after what we’re using, has been shown to be of poor quality? Well, then we spend because we have to fix it. Now we know that there was a problem. That’s not the right kind of thoughtful strategic expenditures, that build secure infrastructure. And there are a lot of reasons we aren’t there yet that have to do with standards, with training with enough historical information to be able to determine risk. We don’t have good metrics. But those things don’t garner the kind of attention where effort and spending is performed. If you think about, at least at the government level, for instance, we have NIST the National Institute of Standards and Technology. It does incredible work in this arena. Talented people great reports and documents, and they’re constantly underfunded, and often ignored by other agencies. We just don’t have the set of incentives and motives to focus attention in the places where it really should go strategically, and that needs to change.

Steve King 20:14

Okay, it seems to me we have plenty of incentive. But I guess it’s not translating.

Eugene Spafford 20:20

Let me inject here because I think what’s important to to recognize about incentive is, we are a very short term focused country. We have elections, every two years for representatives every four years for governors and presidents. And the thinking about what gets done is in a couple year timeframe, so that we have something to show for the next election. in boardrooms, we have people who are appointed to CEO and CEO positions, and their motivation is the next quarter’s return to stockholders. We don’t have a sufficient amount of long term, long baseline thinking. Some of our national level adversaries have 100 year plans. We’re lucky if we can get a two year plan and get it in place and follow through. Because we have changes in leadership and changing priorities. And there’s an immediate need that we have to put money on and where are we going to take it from what we’re going to take it from things that don’t pay off immediately, like investments in cybersecurity, and education. That’s another area that is constantly money is pulled away from because they’re not going to see a result anytime soon. Whereas politically or economically, we have to have immediate results. And that’s another big part of the problem is we have the wrong attitude about where security fits in its overall posture.

Steve King 21:54

Yeah, all of that is great points. And unfortunately, there’s not much I guess, we can do about that. On one front, there is probably something we can do about it. And that is education, you’re in addition to being a legendary expert in cybersecurity, you’re also have the same sort of claim for education as well, you’ve been doing this for quite a few years, you built that fabulous program at Purdue, we know we’ve got this huge skills gap, and every year it continues to widen. If you were to develop an education program, what would it look like? And how would you implement that.

Eugene Spafford 22:31

So the gap we have is for practitioners, largely, and that will continue to widen. Because we just have so many fires breaking out everywhere, we basically need lots of firefighters, we don’t have a sustained push for developing fire resistant material. To use that analogy. We do fund in education, we do have some research that goes on. But an awful lot of that research money is, again towards specific problems, that specific applications, and how well that can be turned into something for the market. If the systems that we had deployed, were more resilient, less flaws in them, and operated more correctly, we wouldn’t need as many people with cybersecurity skills. I was having a conversation with somebody yesterday. And in fact about this. I had heard a story from Dorothy Denning of a book where when the telephone system was introduced in the last century, and more and more people wanted to get telephones. You know, the old style pictures of the operators, the row of operators with a plug boards in front of that was necessary to run the phones. And the phone adoption rate was just so fast that an official for at&t said that if this comes up by the middle of the century, everyone in the US is going to have to be employed as a telephone operator. Well, what happened is that by the middle of this century, everyone was a telephone operator. You look up phone numbers and a phone directory, and you dialed in the number. And you got your call through what had happened is that the technology had been developed to obviate that need for all those people. We can do that with security. If we make the investment in better design, and in better deployment, so that we don’t have to have all these people doing incident response, for instance, or all these people who have to monitor the perimeter from a security operation center, all the time collecting all the logs that simply there because we have so many flaws in what’s deployed.

Steve King 24:57

That’s a fascinating analogy and The issue around education from our point of view here and we’re relaunching our cyber Ed platform, sometime this quarter, is really focused on the cyber warrior class as you indicate in referring to them as firefighters. And we need to be able to transition sort of conventional IT skills into cybersecurity defense skills. You think that’s a reasonable approach?

Eugene Spafford 25:25

Yeah, I think we need a range, we certainly need the technical people who have got the training and the tools to be able to respond on a day to day basis. But we also have to have on the spectrum, we have to have the people who are building systems to understand security. So it doesn’t take a lot to find advertisements for take our 15 week boot camp and become a programmer. Well, those are the people who were building the vulnerable code because they have no training or incentive for providing better security. So we need to have that engineering group to be better trained and better equipped. And then we also have to have researchers who are looking at fundamental questions of how to build security systems, not how to build security into existing systems, which is not something we should ignore, but is in part doomed because of the very models that we’re building on. It bothers me, for instance, that so much of the money that’s spent in research is intended to be how do we build new security features on top of Linux and Windows? using existing chipsets, rather than some fundamental questions about is there a more secure architecture that we could build is that chipset? Is there a more secure operating system design that would meet needs? And do we really need to run the same operating system on the same chip on everything from home systems being used for gaming, two systems onboard naval vessels, tracking air defense? I think that’s part of the problem is that we have decided to adapt everything to common platforms because of existing software base, but the needs the risks, the issues are so different. But we’re not looking at that question that isn’t where the money’s going. That isn’t where the attention is going. So we need that poll range. Yes, we need the responders but we we have to have people who are asking fundamental questions about is this the right way to do things? And then give them the resources to explore options?

Steve King 27:28

Yeah, it seems we’ve been doing that for years with Microsoft. And to your point of layering cybersecurity solutions, one on top the other. There seems to be a reluctance to go back to the drawing board and start over when obviously, that is probably what’s required here.

Eugene Spafford 27:45

Yeah, the idea of using abusing Linux on every IoT device, simply because it’s free, right. But it’s got huge overhead that really isn’t needed and actually provides a bigger attack surface than it should have. We just create new problems for ourselves, because we’re trying to do it cheaply and fast, rather than doing it right.

Steve King 28:05

Yeah. Well follow the money, right? Yep. So you have any predictions for this year that you’d like to share?

Eugene Spafford 28:17

Gosh, I thought about that. If somebody had asked me 12 months ago about predictions for the year, no way, have hit it with with COVID. With the election with the insurrection at the Capitol with solar winds with I mean, we just a range of things that have been been issues. I think that we’re going to see more problems in the cyber realm. Principally, because we’ve had so many more people working from home, who, again, working with tools and training that are not supported with good cybersecurity. So undoubtedly, there have been things happening that haven’t been reported yet we haven’t seen yet. And, of course, we have companies talking about switching to this more as a full time kind of opportunity. So that’s going to cause problems. We’ve been seeing more attacks that are focused on the cloud. I have reservations about recommendations for everybody moving to the cloud, there are new vulnerabilities and problems that are not well understood for many organizations to do that. And that movement is resulting in new attacks being developed in that realm. We’re going to continue to have a lot of controversy over social media because of the splits that have developed and the fact that we have organizations domestically and foreign that are interested in continuing to widen those divides for their own purposes. So those are going to be issues. So I think it’s going to b, a challenging a challenging year from the cybersecurity point of view. And, of course, economically, looking at some of the issues of what the COVID-19 has done and will continue to do to world economy also shifts a lot of priorities and a lot of behavior. So it’s likely to be a challenging year, although I hesitate to make really specific predictions.

Steve King 30:26

Okay, that’s, that’s great. I mean, this has been a fascinating discussion. And I hope that we can get together again, maybe in a couple of months and dig into the cloud vulnerability space, because I agree with you there. There are some amazing similarities between that and some of the things that we’ve rushed into in the past and this crazy digitalization driving all of this behavior.

Eugene Spafford 30:49

Yes, it’s one of those things, too, that again, when I’ve talked to people in a number of small to medium sized companies, and I asked Why are you moving to the cloud? And the answer is, it’ll save us money. At Well, again, that’s failing to think about the bigger picture and a longer term costs. And so we’re going to see more of that. I talk about this with my students on a regular basis. Right now, I’m involved in projects through the State Department to help a few other countries build up some of their cybersecurity training at their higher end. And it’s a difficult problem because they don’t even know where to start, other than their training ethical hackers and penetration testers, which again, is just, that’s at the wrong end of the spectrum. Those are people who look for problems that are already there. Okay. But we really shouldn’t be spending more time on building our system so they don’t have the problems in the first place. I don’t know how we get to that point.

Steve King 31:51

needed to do why. Gene Spafford, thank you again for joining us and taking time out of your schedule. I really appreciate it. This was a fascinating interview. And again, I hope we do this again soon. And thank you to our listeners for joining us in another episode of cyber theories dive into the world of cybersecurity. Until next time, I’m your host, Steve King, signing off.